Most people don’t really care, don’t think it affects them much, and don’t believe the hype

Tom Harris

In a recent interview with the Vatican News service, former U.S. Vice President Al Gore again claimed “the climate crisis is now the biggest existential challenge humanity has ever faced.”

Gore boasted, “I have been fortunate to be able to pour every ounce of energy I have into efforts to contribute to the solution to his crisis.” Ironically, Mr. Gore personally uses vast amounts of energy, often traveling in private jets, SUVs and limousines, and lives in mansions, one of which uses 21 times more electricity than the average American home.

We often hear claims that man-made climate change is our greatest threat. But according to a recent Gallup poll, very few people in the United States actually believe it is. Indeed, even the United Nations own polling reveals that respondents across the world rate climate change last among issues they would like the UN and governments to focus on. No matter how long the list, climate change is always last.

In telephone interviews conducted July 1-11, 2018 with a random sample of 1,033 adults, over the age of 18 and living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, Gallup News Service asked: “What do you think is the most important problem facing this country today?” The question was “open ended,” in that any answer was accepted.

According to the respondents, the top problems facing America were “Immigration/Illegal aliens” (22%) and “Dissatisfaction with government/Poor leadership” (19%). Only 2% of respondents cited “Environment/Pollution.”

This 2% figure included those who mentioned climate change, as well as those who listed other environmental concerns such as ocean pollution, endangered species and toxic wastes. The fraction of Americans who labeled climate change as the nation’s most serious problem must have been very small indeed.

This sort of result is also reflected in July 5 poll reported by the New York Times. Among the main reasons young adults gave for not wanting (or not being sure they wanted) children, worries about climate change ranked #13 out of 19 reasons given. The first three reasons cited were “Want leisure time,” “Haven’t found partner,” and “Can’t afford child care.”

While other polls show varying levels of public concern about climate change, when people are asked to prioritize issues, climate change often does not rate highly. Even in 2014, just before then-President Barack Obama addressed the heavily publicized UN Climate Summit 2014 in New York City, Pew Research polling indicated that Americans did not consider climate change to be among the top six threats facing the country.

The UN’s own survey confirms that this trend is even more prominent internationally. After polling 9.7 million people from 194 countries, the UN’s My World global survey finds that “action taken on climate change” rates last out of the 16 suggested priorities for the agency. This despite the fact that on the survey website, the UN lists climate change action as the first choice given respondents. Access to reliable energy, better healthcare, government honesty, a good education, etc., are apparently far greater concerns to people across the world.

This should not be a surprise. In contrast to vitally important issues people must deal with on a daily basis, concerns about man-made climate change are based merely on a theoretical hypothesis, not what is happening now or even in the recent past. After all, even NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies asserts that the Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change from 1880 to 2017 is only just over one degree Celsius despite a reputed 40% rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) content. And the impact of further CO2 rise diminishes as the concentration increases.

It is not known whether the rate of sea level rise has increased or not. However, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s U.S. state-wide extreme weather records database, probably the best of its kind in the world, there has been no increase in extreme weather. So, the primary rationale for “action taken on climate change” through expensive restrictions to CO2 emissions is merely the possibility of dangerous climate change in the future. And this is based on computer models of future climate states, models that have failed to forecast what has actually happened.

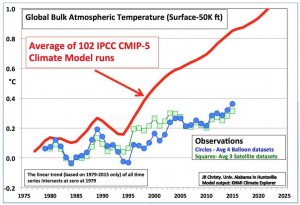

Dr. John Christy is Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science, Alabama State Climatologist and Director of the Earth System Science Center at The University of Alabama in Huntsville. During his February 2, 2016 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space & Technology, he presented a graph that dramatically demonstrates how far apart computer model temperature forecasts differ from what has actually been measured by satellites and weather balloons.

In fact, as of 2016, there was already a 0.5 degree Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) difference between real-world temperatures and the “runaway” temperature predicted by averaging 102 climate model estimates. And yet those faulty models have become the basis for countless claims of imminent climate doom – and the foundation for policies that would replace abundant, reliable, affordable fossil fuel energy with sporadic, unpredictable, weather-dependant, expensive wind, solar and biofuel energy.

Five-year averaged values of annual mean global mid-tropospheric temperature as depicted by the average of 102 IPCC CMIP5 climate models (red), compared to the average of 3 satellite datasets (green – UAH, RSS, NOAA) and 4 balloon datasets (blue, NOAA, UKMet, RICH, RAOBCORE).

Christy told Congress, “[T]hese models failed at the simple test of telling us ‘what’ has already happened, and thus would not be in a position to give us a confident answer to ‘what’ may happen in the future and ‘why.’ As such, they would be of highly questionable value in determining policy that should depend on a very confident understanding of how the climate system works.”

To create the models requires vast amounts of weather and climate data. We also need to input accurate data as the starting conditions for model-generated forecasts to be performed.

However, the collection and interpretation of the necessary data has only just begun, says former University of Winnipeg professor and historical climatologist Dr. Tim Ball. But there are relatively few weather stations that have temperatures records of adequate length or reliability on which to base model forecasts of future climate, Ball explains.

Referring to former-President Barack Obama’s worries about dangerous future climate change, Ball concludes, “Obama’s worries therefore have absolutely no credibility in the real world.”

Ball is not alone in holding this view. Extensive analyses and reports by the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC) summarize thousands of studies from peer-reviewed scientific journals that debunk or cast serious doubt on the hypothesis that emissions of CO2 from human activities will cause catastrophic climate change.

Yet there is nothing hypothetical about the issues that Americans, and people all over the world, list as their top priorities. Problems with immigration and government are happening right now in America.

The issues rated highest in developing countries like Nigeria (2,735,062 Nigerians voted in the UN poll) are similarly pressing: access to a good education, better healthcare, better job opportunities, better transportation and roads, political freedom, affordable and nutritious food.

All are immediate concerns – today, to real people who understand that the world has real problems to solve: problems that affect our lives and well-being right now.

They realize we don’t have the time, money or manpower to obsess over problems that exist only in computer models, questionable news stories, or the fertile imaginations of multi-millionaires like Al Gore.

Tom Harris is Executive Director of the Ottawa, Canada-based International Climate Science Coalition.