The society’s misleading claims about a climate crisis in the Arctic must be corrected

Robert W. Endlich

The January-February 2016 issue of Audubon Magazine (Figure 1) proclaims “Arctic on the Edge: As global warming opens our most critical bird habitat, the world is closing in.” In reality, the magazine’s writers and editors have gone over the edge, with wildly misleading “reports” on the Arctic.

The magazine is awash in misstatements of fact and plain ignorance of history, science and culture. It epitomizes the false claims that characterize “news coverage” of “dangerous manmade climate change.” The following analysis corrects only some of the most serious errors, but should raise red flags about most every claim Audubon makes.

The first part of this issue devotes pages to each of the countries surrounding the Arctic Ocean. The Finland page says “storms become more severe” with warming. The writers are either clueless or intentionally misleading; they likely did not take Earth Science or Meteorology and are oblivious of atmospheric fluid dynamics.

The pole to equator temperature difference drives the strength of storms. If there actually is Arctic warming, that temperature difference declines, and storm strength becomes less severe – not more so.

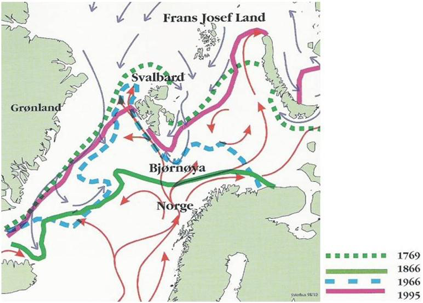

Figure 2. Map showing maximum (April) sea ice extension in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic (Norwegian Polar Institute 2000). The map is based on a database on sea ice extension in the area shown during the past 400 years, to a high degree based on written records found in ships logbooks.

The Norway page describes the Black-legged Kittiwake and speculates that warming in the Barents Sea attracts herring which feed on Kittiwake prey. The authors are clearly unaware that natural warming and cooling cycles have been occurring for centuries. On a map derived from the Norwegian Polar Institute’s examination of ship logs (Figure 2), a green dashed line depicting reduced Nordic Sea ice extent demonstrates extensive warming in the Barents Sea in 1769. During that particular warm period, ocean currents and weather conditions made Svalbard and even parts of Novaya Zemlya ice-free.

The Greenland page purports to show “Greenland Warming.” However, it was warmer than today during the Medieval Warm Period, and abundant new ice formed in Greenland during the past century. Enough snow and ice accumulated on the Greenland Ice Sheet that Glacier Girl, the P-38 airplane that landed there in 1942, was buried in 268 ft of ice before she was recovered in 1992. That’s 268 feet in 50 years, well over 5 feet of ice accumulation a year, much of it during a period when Earth was warming and Greenland was supposedly losing ice.

Audubon’s cover photo features a Russian oil rig amid an ice-covered Arctic Ocean. It is intended to instil fear, by suggesting that a once solidly icy Arctic is melting rapidly. However, history shows that the Nordic ice extent has been decreasing since at least the 1860s, and probably since the depth of the Little Ice Age, around 1690. In fact, historic data, indicate that multi-decadal variability of Nordic Sea extent (some 30-45% more or less ice during each cycle) has been occurring for over 150 years.

Toward the end of the January-February issue is an account of a visit to Wainwright, Alaska, an Inupiat village of about 556 natives, located on the Arctic Ocean in North Slope Borough. The Native Inupiat much prefer to maintain their subsistence culture, which has been their tradition since their ancestors settled nearby about 13,000 years ago.

The caption to the Audubon photograph of the village emphasizes rising ocean waters. However, most of Alaska has falling sea levels, the result of the isostatic adjustment of northern North America. This rebound effect began with the melting of the Wisconsin Ice Sheet, as Earth emerged from the Wisconsin Ice Age and entered the Holocene between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago. The nearest tide gage to Wainwright is Prudhoe Bay, and sea level rise there is very small: 1.20 mm/year +/- 1.99 mm/year (up to 7.9 inches per century) – so small that sea levels might actually be falling there, as well, when margin of error is considered.

The Audubon writers mention “melting permafrost” numerous times, but when the Natives spoke about this in 1979, they clearly did not view it as a problem. In fact, in their own words, recorded in The Inupiat View, the Natives specifically say melt water is scarce in North Slope Borough. What has happened in the years since?

First, the North Slope has a summer, and from early June until mid-September air temperatures average warmer than 32 degrees F. Wainwright’s extreme maximum once reached 80 degrees Fahrenheit! During summer, the soil melts, creating an “active layer.” The surface is not permanently frozen, but is melted part of the year, every year. Whether there actually is problematical “melting permafrost,” as claimed by Audubon, can be determined only by finding the long-term trend in the thickness of the active layer.

Specialists studying this phenomenon publish reports in the Circumpolar Active Layer Monitoring Network, in NOAA’s annual Arctic Report Card, and elsewhere. The 2012 Report Card edition had an extensive section on permafrost. A quote from this edition pours freezing water on Audubon’s “melting permafrost” claim: “Active-layer thickness on the Alaskan North Slope and in the western Canadian Arctic was relatively stable during 1995-2011,” it notes.

The NOAA Arctic Reports do have a heavy dose of alarmist rhetoric, especially in the boilerplate introductory sections, but the actual measurements and data present nothing that supports the alarmist polemic of the day. The long term pattern shows centuries-long slow warming, with multi-decadal fluctuations; significant or alarming anthropogenic trends are simply not there.

Audubon should stay away from areas where it has no expertise – specifically imagined or invented catastrophic anthropogenic global warming. Audubon’s equivocal policy on wind power ostensibly calls on wind energy developers to consider planning, siting and operating wind farms to avoid bird carnage; the Society claims to support “strong enforcement” of laws protecting birds and wildlife. On the other hand, the same Audubon policy speaks about “species extinctions and other catastrophic effects of climate change” and “pollution from fossil fuels.”

When read together, this schizophrenic policy clearly puts Audubon on the side of climate alarmism – with the loss of birds and bats merely a small price to pay in an effort to “save the planet.”

Another article shows that Audubon’s alarmist climate claims, rather than bird safety, clearly dominate president David Yarnold’s concerns. Beneath a picture of a forest fire, an editorial quotes him: “Climate change is the greatest threat to birds and biodiversity since humans have been on the planet.”

Yarnold’s editorial is rife with alarmist propaganda: increasing drought (data show drought decreasing in the United States over the past 110 years in regions where we have temperature and rainfall measurements) … increasing forest fires (not so, according to actual data) …increasing species extinctions (virtually no extinctions have occurred except on isolated islands where predators were introduced by humans) … and more flooding (there has been nothing outside normal experience).

Audubon needs to concentrate on saving birds and other flying creatures from the very real death machines that kill countless thousands, perhaps millions, of them every year. These killing machines include wind turbines, that chop up raptors, song birds and bats, and heliostats (installations using mirrors to concentrate the sun’s rays) that incinerate them.

Bats pollinate crops and consume insects. However, the number of bats killed has been conservatively estimated at 600,000 annually, and may be as high as 900,000. The Ivanpah solar-to-electrical-energy plant in California’s Mojave Desert actually ignites birds in flight; the dying birds are called “streamers,” because they emit smoke as they fall from the sky. One report estimates that over 100 golden eagles and 300 red tailed hawks are killed yearly by wind turbines at California’s Altamont Pass, but another calculates that millions of birds and bats are killed every year by US wind turbines.

Audubon needs to get some real science in its research and show true empathy for the human-caused deaths that our flying friends face on a daily basis

Robert Endlich served as a weather officer in the US Air Force for 21 Years. He has a BA in geology and an MS in meteorology and is a member of Chi Epsilon Pi, the national Meteorology Honor Society. (A more extensive version of this article can be found on MasterResource.org)